From Poland and France to the US, rightwing populist parties dominate rural and post-industrial hinterlands while the centrist liberal vote is concentrated in cities. This urban-rural divide is arguably the main political fault line in Europe and North America today.

It appears the backlash against globalised capitalism is strongest when associated with rural conservatism and xenophobia against migrants. But anti-urban populism has not always been – and perhaps isn’t now – a simple reaction against the forces of modernity.

In my new book, The Last Peasant War: Violence and Revolution in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe, I explore how peasant movements in eastern Europe during the first half of the 20th century often combined deep resentment of cities with aspirations for radical social and economic change. These movements aimed to create a more egalitarian countryside while enhancing its influence and prosperity.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The first world war was the main catalyst. Warring countries in central and eastern Europe introduced harsh controls of the rural economy to secure food for armies and the urban labour force. Villagers working small plots of land resented these measures and the cities that dictated their terms.

Confronted with shortages at home and death at the front, hundreds of thousands of peasants deserted from the poorly led armies of Austria-Hungary and Russia. In Austria-Hungary, and later in the Russian civil war, scores of thousands of armed peasant deserters banded together to form motley “green” forces based in forests and hilly areas.

These men, along with recently demobilised soldiers, led a wave of bloody violence in many areas of the east European countryside as the old empires disintegrated. Large estates were sacked, officials chased off, and Jewish merchants robbed and humiliated. Peasant crowds often targeted towns as the places that appeared to mastermind and benefit from their exploitation.

In most places, the unrest did not last long. Yet the deserter movements and other forms of rural wartime resistance galvanised interwar agrarian politics – that is, politics concerned with the cultivation and distribution of land – on a scale not seen before or since.

Peasants demanded the breakup and redistribution of large estate land, the end of wars led by parasitic cities, representation of peasants in national governments proportionate to their numbers, and local autonomy.

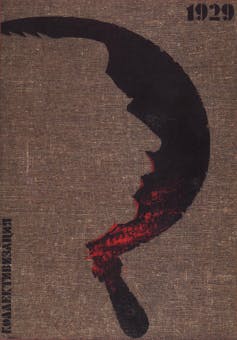

These were undeniably revolutionary goals. The Russian Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin and his followers were forced to revise the mainstream Marxist view of a backward peasantry. His government legalised land seizures by peasants with a 1917 decree before reintroducing the despised wartime economy and later concluding an uneasy truce with the countryside during the 1920s. The war against the Soviet peasantry was finally won during Stalin’s brutal collectivisation drive in the early 1930s.

Many ambitious peasant initiatives remained isolated from each other: village republics sprouted up in parts of the former Habsburg and Romanov empires with the chief aim of redistributing large estate land.

As the new countries of east central Europe consolidated their power, they faced competition from micro-states in parts of Croatia, Slovenia and Poland. Many short-lived republics were reported across Ukraine and European Russia.

More durable were the rural populist parties that became a defining feature of east European politics. From 1919 to 1923, Bulgaria was ruled by the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union under Aleksandar Stamboliyski, who introduced far-reaching reforms to elevate and reward agricultural work before he was murdered in a coup.

In the former Habsburg lands, agrarian politics mushroomed in the aftermath of the first world war, influencing national politics through the end of the second world war. The peasant masses looked to the Polish People’s party, the Croatian Peasant party, and others to lead them forward on a “third way” to modernity, avoiding the pitfalls of both heartless liberalism and tyrannical communism.

Eastern European governments implemented agrarian reform to benefit land-hungry villagers, but it fell short of expectations. Later, the rise of authoritarian regimes across much of the region by the early 1930s forced many peasant movements out of parliamentary politics. Politically marginalised, reeling from the Great Depression, millions of villagers embraced extremist politics, fascism included.

But Hitler’s occupation of much of eastern Europe found little support among them. Large numbers of peasants joined or supported resistance movements, tipping the scales against the axis forces in Yugoslavia. In Poland, the rural populists had their own armed resistance numbering in the hundreds of thousands: the Peasant Battalions.

By around 1950, peasant revolution was extinguished in Europe. Collectivisation in the east and mechanisation across the continent altered the fabric of rural life. Tens of millions left the land for cities, never to return.

The politics they backed in the era of world wars are now a distant memory. At the time, city dwellers looked at them with a mixture of fear and puzzlement. How, they asked, could men like Stamboliyski and Stjepan Radić of the Croatian Peasant party rail against city life while claiming they wanted to make their societies more equal and prosperous?

Then, as now, the world beyond the metropolis nurtured sentiments far more radical than we often assume.