Human trafficking on TikTok: Smugglers defy Trump with offers on the social media platform

People traffickers use the network to attract migrants who are seeking to cross into the United States without documents

When you click on the video, a corrido — a Mexican narrative ballad — plays: “And here I have an express consulate / Where we send people to the USA / There are no procedures, visas, or passports here.”

The catchy tune plays over images of people — presumed to be undocumented immigrants — speaking in front of the camera (although what they say cannot be heard). Lines in the middle of the screen read: “I’m already at the ranch in El Paso, Texas, thank God. The crossing is safe. More info available privately.”

In case it wasn’t clear, an emoji of a small yellow chicken serves as a final point to confirm that this week-old TikTok post is an advertisement for a pollero or coyote — slang for smuggler — who offers his services to traffic undocumented people into the United States. Hundreds of similar videos have popped up on the social media network.

When you scroll through the content, there’s no trace of the name that’s been on everyone’s lips for months: Donald Trump.

Judging by the videos uploaded daily to TikTok, human trafficking remains lucrative. However, two months after his return to the White House — and after beginning his crusade against undocumented immigrants — the flow of people crossing the border from Mexico into the United States (through the desert, by river, under the wall, or by road) has dropped dramatically.

The U.S. authorities proudly share that border apprehensions have been reduced to “historic lows.” This past February, there were only 8,000 encounters with migrants at the border, a 94% reduction compared to the same month a year earlier. This is evidence that the crude deterrence strategy — deployed with stories of raids and arbitrary detentions, images of migrants in shackles being sent back to their countries, or agreements to send deportees to President Nayib Bukele’s infamous prisons in El Salvador — is working. People no longer want to take the risk. Some have even taken the opposite route, heading back to the south from where they came. But not everyone.

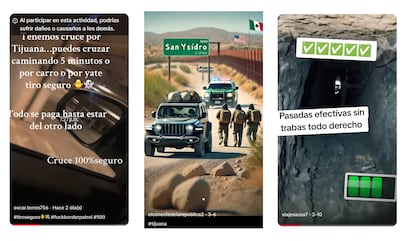

Those who know the ins and outs of what is perhaps the most talked-about border in the world — the coyotes — continue to offer their services. And they’re doing so with promotional videos on TikTok, the social media platform of the moment. Some videos depict animated cartoon airplanes, cars, or boats traveling northward, through the countries on the map. Others — clearly generated by artificial intelligence — show images of the border wall, with cars parked next to it and people stepping through the metal slats.

You can also see supposedly real crossings of people running through a field of dry brush, walking through long tunnels, or driving across the border (something that seems implausible). The most basic videos, however, simply display images of airplanes with text above them, stating that the transport service includes meals, guides, tickets, hotels, etc. Corridos — part of a musical genre that was born along the vast U.S.-Mexico border — are the most common soundtrack.

But most of the videos are of people — in groups, or alone — speaking to the camera. “Today, March 12, at 9:55 a.m. we’re in El Paso, Texas, thanks to Juan,” one man after another says, in a serious tone. The same marketing strategy is used by “El Flako,” a user who published a video a couple of days ago. The footage shows five women and one man in what appears to be a hotel room.

“Hello! Today, March 17, we arrived in McAllen (Texas). Thank you very much to our guides, to the people who accompanied us; you treated us very well. We arrived very safely. Thank you for the Coca-Cola. Thank you for the water, for all the attention,” a woman — with a Colombian accent — says cheerfully. After the camera pans around — capturing the smiling people — another woman closes the ad with a guarantee: “Excellent service.”

The advertising strategy is transparent. It aims to promote a service that often inspires fear in potential customers, due to its well-known association with organized criminal networks. Many accounts define themselves as travel agencies and seek to give the appearance of legitimate, trustworthy businesses. But the doubts aren’t completely dispelled: there’s no way to verify that people are actually where they claim to be. And, in many videos, it’s clear that the message is delivered under some form of coercion.

In any case, the reality is that — in this business — the customer has no leeway to make demands. Guarantees are worthless. By hiring a service, people are blindly surrendering to what could be a human-trafficking network: they risk being kidnapped, abandoned along the way, or even killed. Each year, hundreds of people die while crossing over from Mexico into the United States.

Smuggling is a business. And, for those interested, the initial treatment is usually friendly, helpful and very clear. “Yes, my brother, tell me what’s up,” the user — who calls himself “El Flako” — replies to a message. “For your destination, I’m charging $5,000 from Mexico City. If you go to New York, the price goes up to $7,000. The guarantee is that you only pay $1,000 when I pick you up. You pay the rest at your destination,” he explains, through the TikTok chat. He then provides his phone number to shift the conversation to WhatsApp, which is more secure because it’s encrypted. Payments can be made via bank transfer, he assures the interested party.

When asked if the service involves walking through the desert, El Flako replies: “No, I don’t cross the desert. My job is to get you there by truck or by yacht.”

Upon further questioning, however, the story becomes more complicated. The smuggler offers to cross the person by yacht through Mexicali, a city that has no ocean or river access. If they choose to go through Laredo, Texas, the crossing is supposedly by boat, while a pickup truck or car will take the client to Houston. And, from there, another car will get them to their final destination.

The conversation with the account — which is named “Trips to the USA” — immediately moves to WhatsApp. “Don’t worry, friend,” he writes, reassuring the user, who’s nervous about Trump’s iron fist. In a rapid sequence of messages, he explains that the first part of the trip is to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, where they’ll rest. Room and board are included. After that is when the “jump” will take place: they’ll cross the border to El Paso, Texas, where someone else will be waiting to transfer the migrant to their final destination.

Following these details, a woman provides even more information in a voice note: “Look, I’ve gone over the bridge by car, through the culvert, and through a tunnel and a wall. [You don’t have to cross] hills, rivers, or jump over walls. [You can go under] the wall, or you cross the bridge by car. You cross safely and with papers.” The prices are similar. By tunnel: $6,000. By bridge, with false papers: $7,500. For a destination other than El Paso, an additional $2,500 is added.

It could hardly be simpler. “When do you want to travel? We have daily departures,” the people behind the accounts insist.

For several years, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and authorities in the affected countries have been aware that social media is being used for human smuggling. But users know how to evade security forces, for example, by switching to encrypted messaging services, so that they can chat freely. TikTok, for its part, claims that human trafficking is prohibited on its platform and that it reports any cases it encounters. However, the proliferation of accounts that promote human-trafficking casts doubt on this claim.

The rise of this advertising on TikTok came after the pandemic, when smugglers realized that they could reach their potential customers more easily there, after spending years on other platforms like Facebook or Instagram. The explosion of the Darién Gap route, for example, was largely due to videos of migrants — who recounted how they had crossed the jungle — going viral. TikTok opened a door that had always been closed. The coyotes have simply been following the trends.

The content of the most recent videos also demonstrates this. Those published months ago — when Joe Biden was still president of the United States — advertised crossings with appointments to request asylum through the CBP One app. That service is no longer offered now, with Trump in power and the app converted into CBP Home, a “self-deportation” app.

Although it may not seem so based on the videos, business has suffered. A human trafficker — identified only as “Don Luis” — briefly answers EL PAÍS’s questions about this. He claims that business has dropped by 80% in recent months.

And prices? They’ve dropped too, he notes. It’s basic supply and demand. A few months ago, some media outlets reported that crossings were going for up to $18,000. If those reports are true, this represents a 60% drop in prices. With Trump’s arrival and the militarization of the border — on both the U.S. and Mexican sides — the routes have also changed, according to this people smuggler.

It’s paradoxical. Smugglers have been forced to plunge even deeper into the shadows and deepen their underground networks to evade the U.S. Border Patrol. But, at the same time, they use TikTok, as if they’re legitimate businesspeople, selling their services in broad daylight. And, in the middle of all of this, there’s a migrant seeking to reunite with his family, or another trying to support her loved ones, who are thousands of miles south.

There are countless stories of people who are ignoring the will of the man who signs executive orders in the Oval Office. They often begin their journeys after reading TikTok posts. One such message reads: “We continue working, we continue fulfilling dreams, always with the hand of God, [...] with direct crossings to the U.S.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.