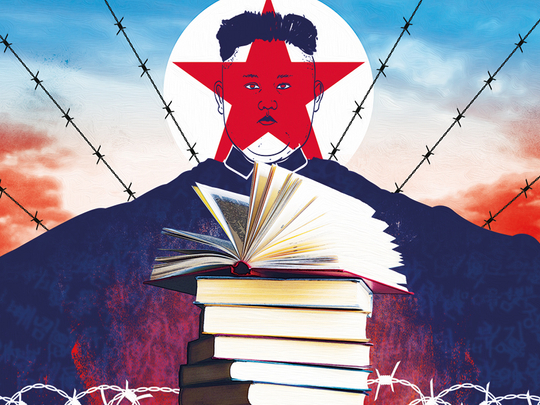

North Korea may be the most secretive and totalitarian country in the world, as well as the wackiest. As a result, it inspires some of the best fiction and nonfiction, so the upside of the risk of nuclear war is an excuse to dip into literature that offers glimpses of this other world — and some insights into how to deal with it.

Thousands of North Koreans have fled their homeland since the famine of the late 1990s, and many are writing memoirs recounting their daily lives and extraordinary escapes. A leading example is In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl’s Journey to Freedom (Penguin) by Yeonmi Park, with Maryanne Vollers. Park is a young woman whose father was a cigarette smuggler and black market trader. As a girl, she believed in the regime (as did her mother), for life was steeped in propaganda and anti-Americanism. Even in her math class, “a typical problem would go like this: ‘If you kill one American and your comrade kills two, how many dead Americans do you have?’”

What opened Park’s eyes was in part a pirated copy of the film Titanic. The government tries hard to ban any foreign television, internet or even music, and North Korean radios, which don’t have dials, can receive only local stations. But the black market fills the gap, with handymen who will tweak your radio to get Chinese stations, and with illegal thumb drives full of South Korean soap operas.

I’m among those who argue that we in the West should do more to support this kind of smuggling, because it’s a way to sow dissatisfaction. Indeed, what moved Park was the love story in Titanic: “I was amazed that Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet were willing to die for love, not just for the regime, as we were. The idea that people could choose their own destinies fascinated me. This pirated Hollywood movie gave me my first small taste of freedom.”

In the end, Park’s father was arrested for smuggling, and the family’s life collapsed. Park and her sister went hungry and had to drop out of school, and she survived eating insects and wild plants.

So at 13, Park and her mother crossed illegally into China — and immediately into the hands of human traffickers who were as scary as the North Korean secret police. They raped her mother and eventually Park as well, and both struggled in the netherworld in which North Koreans are stuck in China — because the Chinese authorities regularly detain them and send them home to face prison camp. Park and her mother were lucky, finally managing to sneak into Mongolia and then on to South Korea.

Heroic propaganda

Another powerful memoir is The Girl With Seven Names: A North Korean Defector’s Story (William Collins) by Hyeonseo Lee, with David John. She is from Hyesan, the same town as Park. It’s an area on the Chinese border where smuggling is rampant, where people know a bit about the outside world and where disaffection, consequently, is greater than average.

Still, Lee’s home, like every home, had portraits of the country’s first two leaders, Kim Il-sung and his son, Kim Jong-il, on the wall. (The grandson now in power, Kim Jong-un, hasn’t yet made his portrait ubiquitous.) Lee begins her story recounting how her father dashed into the family home as it was burning to rescue not family valuables but rather the portraits of the first leaders. There’s an entire genre of heroic propaganda stories in North Korea of people risking their lives to save such portraits.

Like other children, Lee grew up in an environment of formal reverence for the Kim dynasty. At supper, she would say a kind of grace — to “Respected Father Leader Kim Il-sung” — before picking up her chopsticks.

“Everything we learned about Americans was negative,” she writes. “In cartoons, they were snarling jackals. In the propaganda posters they were as thin as sticks with hook noses and blond hair. We were told they smelled bad. They had turned South Korea into a ‘hell on earth’ and were maintaining a puppet government there. The teachers never missed an opportunity to remind us of their villainy.

“‘If you meet a Yankee on the street and he offers you candy, do not take it!’ one teacher warned us, wagging a finger in the air. ‘If you do, he’ll claim North Korean children are beggars. Be on your guard if he asks you anything, even the most innocent questions’.”

Hmm. No wonder my attempts at interviewing North Korean children have never been very fruitful.

Lee escaped to China at age 17 and started a new life in Shanghai, but remained in touch with her family. One day, her mum called from North Korea. “I’ve got a few kilos of ice,” or crystal meth, she said, and she asked for Lee’s help in selling it in China. “In her world, the law was upside down,” Lee says, explaining how corruption and cynicism had shredded the social fabric of North Korea. “People had to break the law to live.”

It’s fair to wonder how accurate these books are, for there’s some incentive when selling a memoir to embellish adventures. I don’t know, and in the case of In Order to Live, sceptics have noted inconsistencies in the stories and raised legitimate questions.

So how did North Korea come to be the most bizarre country in the world? For the history, one can’t do better than Bradley K. Martin’s magisterial Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty (St. Martin’s Griffin). Martin recounts how a minor anti-Japanese guerrilla leader named Kim Il-sung came to be installed by the Russians as leader of half of the Korean peninsula they controlled after the Second World War. Martin discovers that Kim’s father was a Christian and a church organist, and Kim himself attended church for a time. That didn’t last, and Kim later banned pretty much all religion. But do North Koreans believe in such a view?

‘Revenge against the Yankee vampires’

Judging from defectors I’ve interviewed and much of the literature on North Korea, many do — especially older people, farmers and those farther from the North Korean border. That’s partly a tribute to the country’s shameless propaganda, which B.R. Myers explores in his interesting book, The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves — And Why It Matters (Melville House). He notes that North Korea produced a poster showing a Christian missionary murdering a Korean child and calling for “revenge against the Yankee vampires” — at the same time that the United States was the country’s single largest donor of humanitarian aid. Myers argues that North Koreans have focused on what he calls “race-based paranoid nationalism”, including bizarre ideas about how Koreans are “the cleanest race” — hence the title — bullied and persecuted by outsiders.

For a more sympathetic view of North Korea’s emergence, check out various books by Bruce Cumings, a University of Chicago historian, like Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (W.W. Norton). Cumings argues that North Korea is to some degree a genuine expression of Korean nationalism. I think Cumings is nuts when he says: “It is Americans who bear the lion’s share of the responsibility” for the division of the Korean peninsula. But his work is worth reading — unless you have high blood pressure, in which case consult a physician first.

Whatever the uncertainties about the accuracy of recent North Korean memoirs, it’s absolutely clear that some stories about North Korea are fabricated — because they’re fiction. Today’s political crisis with Pyongyang is a great excuse to read Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son (Random House), which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2013. Johnson tells the story of a military man turned prisoner turned celebrity turned villain, dealing for a while with utterly confused American visitors — an account so implausible and bizarre that it’s a perfect narrative for North Korea.

The other fiction that I’d recommend is the Inspector O series by James Church, the pseudonym of a well-respected western intelligence expert on North Korea. Inspector O is a North Korean police officer who investigates murders, a bank robbery and various other offences, periodically dealing with foreigners and turning down chances to defect.

Inspector O is a complex, nuanced figure who understands that the regime he serves is corrupt, brutal and mendacious, but he remains loyal. That’s because he is a deeply patriotic and nationalistic Korean, and he resents the patronising scorn of bullying westerners. I think many North Korean officials today are an echo of the conflicted nationalist Inspector O.

— New York Times News Service

Nicholas Kristof is an American journalist, author and a winner of two Pulitzer Prizes.